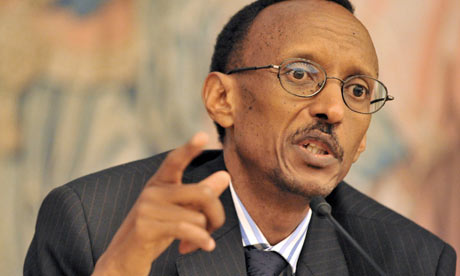

Paul Kagame has faced charges that his regime is increasingly authoritarian after the opposition was effectively barred from challenging him in August’s presidential election. Photograph: Uwe Anspach/EPA

Paul Kagame has faced charges that his regime is increasingly authoritarian after the opposition was effectively barred from challenging him in August’s presidential election. Photograph: Uwe Anspach/EPATony Blair has defended his close personal and working relationship with one of Africa’s most controversial leaders, Rwanda‘s Paul Kagame, even as foreign governments distance themselves over accusations of war crimes and the suppression of political opposition.

Blair has described Rwanda’s president as a « visionary leader » and a friend after making the central African country the focus of the work of his charity, the Africa Governance Initiative (AGI), to turn around the continent’s fortunes.

The initiative includes placing officials hired by Blair in Rwanda’s institutions such as the president’s policy unit, the prime minister’s office, the cabinet secretariat and the development board to assist with administration. Blair is leading a similar programme in Sierra Leone and Liberia, and says he intends to expand it to other African countries.

But the relationship has come under increasing scrutiny following a UN report that accused Kagame’s forces of war crimes, including possibly genocide, in the east of Democratic Republic of Congo, and charges that the Rwandan government is increasingly authoritarian after the opposition was effectively barred from challenging Kagame in August’s presidential election. The White House has criticised Kagame for the suppression of political activity and made clear that it does not regard Rwanda as democratic.

But Blair said allowances have to be made for the consequences of the 1994 genocide of hundreds of thousands of Tutsis and suggested that Kagame’s economic record outweighed other concerns.

During a recent visit to Washington to meet the US secretary of state, Hillary Clinton, and promote his Africa initiative, Blair told the Guardian: « I’m a believer in and a supporter of Paul Kagame. I don’t ignore all those criticisms, having said that. But I do think you’ve got to recognise that Rwanda is an immensely special case because of the genocide. Secondly, you can’t argue with the fact that Rwanda has gone on a remarkable path of development. Every time I visit Kigali and the surrounding areas you can just see the changes being made in the country. »

Kagame, pictured below, has been a particular favourite of Britain. Blair’s former development secretary, Clare Short, directed large amounts of aid to Rwanda and lavished praise on Kagame. Rwanda also recently joined the Commonwealth.

For many years, Kagame, a Tutsi who led the forces that ended the genocide, was praised by other leaders – Bill Clinton called him « one of the greatest leaders of our time » – amid continuing guilt over the major powers’ failure to stop the murder of the Tutsis and out of a belief that he had brought relative stability to a troubled region.

But the publication of a UN report in October accusing Rwanda of war crimes in eastern Congo, including the wholesale massacres of Hutu civilians and the plunder of minerals, tarnished Kagame’s image. He has vigorously denied the accusations but human rights groups have been documenting such crimes for years.

Blair rolled his eyes at mention of the UN report, which he questions, and suggested that Rwanda’s occupation of eastern Congo for many years was justified by the continuing threat from Hutu extremists.

« He (Kagame) and I specifically discussed this, » Blair said. « They [the Rwandan government] very strongly push back against the allegations that are made.

« You’ve got to understand that it’s a very difficult situation in Congo because you’ve got the rival forces fighting each other and that’s spilling across into his territory. »

Kagame has also been forced on the defensive over his re-election in August, with 93% of the vote, after his main rivals were jailed and barred from running after being accused of stirring up ethnic hatred between Hutus and Tutsis after what Human Rights Watch called « persistent harassment and intimidation » of their parties by the government, and the curbing of criticism in the press including the banning of two newspapers. The deputy leader of a third opposition party was murdered in July.

There is a growing perception among human rights groups that Kagame has used accusations of « divisionism » and « genocide ideology » to suppress legitimate political criticism. But Blair said the Rwandan government’s sensitivity is justified because of the country’s recent history.

« When they get upset about any form of politics that leaches at all into ethnic rallying cries, it’s for a reason, » he said. « You can’t just dismiss that reason. I don’t ignore these criticisms at all. Indeed, I’ve discussed these with the president. He’s someone I’ve got to know well and I’m a believer in him, and I believe I won’t be disappointed.

« You’ve got to make a judgment about this, and my judgment, rightly or wrongly, is that he is somebody who does want to do his best for his country, is doing his best for his country, and is a huge focus of stability in a place that still desperately needs it when we’re only 16 years after the genocide. »

However, there is also concern that a rising generation of Hutus will increasingly feel shut out of the political process, deepening ethnic divisions once again as extremists revive accusations of Tutsi domination.

Governing principles

Tony Blair’s Africa Governance Initiative (AGI) is one of a series of programmes the former prime minister is juggling on the world stage, along with his duties as a Middle East envoy, for his faith foundation, a climate change initiative and a foundation to promote sport.

The AGI, a registered charity, launched its first project in Rwanda in 2008 and provides the model for similar programmes in Liberia and Sierra Leone, both rebuilding after devastating civil wars. It involves placing Blair’s staff in high government offices, such as presidential policy units and cabinet secretariats, to build « effective governance » through « a combination of on-the-job coaching and support and formal and informal training ».

Blair says a key to its success is a new generation of African leaders not hidebound by history.

« There is a clear sense by this generation of African leaders that the future of Africa is in their hands and they’re not interested in a debate about the colonial past, » he said. « They’re very much eager to get their countries sorted out. They’re perfectly willing to listen and learn from the outside. They’re also keen on bringing in quality private sector investment and that is the way you build a country. »

But the initiative is open to criticism for promoting a model that pressures African states to again surrender political and economic autonomy.

By Chris McGreal in Washington

guardian.co.uk © Guardian News and Media Limited 2011

The AGI, a registered charity, launched its first project in Rwanda in 2008 and provides the model for similar programmes in Liberia and Sierra Leone, both rebuilding after devastating civil wars. It involves placing Blair’s staff in high government offices, such as presidential policy units and cabinet secretariats, to build « effective governance » through « a combination of on-the-job coaching and support and formal and informal training ».

Blair says a key to its success is a new generation of African leaders not hidebound by history.

« There is a clear sense by this generation of African leaders that the future of Africa is in their hands and they’re not interested in a debate about the colonial past, » he said. « They’re very much eager to get their countries sorted out. They’re perfectly willing to listen and learn from the outside. They’re also keen on bringing in quality private sector investment and that is the way you build a country. »

But the initiative is open to criticism for promoting a model that pressures African states to again surrender political and economic autonomy.

By Chris McGreal in Washington

guardian.co.uk © Guardian News and Media Limited 2011

Posted by rwandanews